Know the difference between operational and embodied carbon

By John Holbert

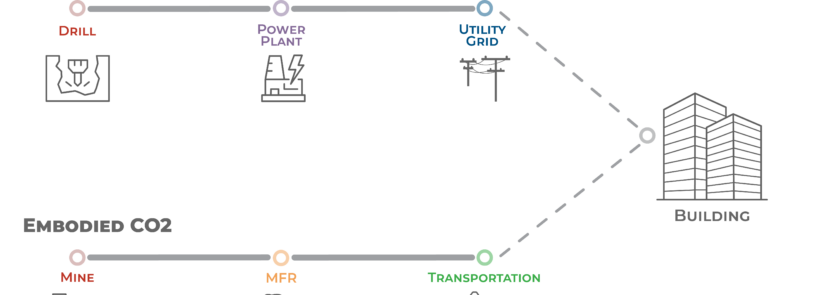

In the built environment, carbon emissions come from two main sources: operations (i.e., energy use) and materials (such as construction materials), both of which contribute to the carbon problem.

Operational carbon emissions in the built environment are caused by greenhouse gases generated during daily activities. In schools and on campuses, these emissions mostly result from heating and cooling water and air, typically by burning carbon-based energy. Even when schools and campuses don’t burn carbon-based energy on site and rely entirely on grid electricity, about 61 percent of the grid is currently supported by carbon-based fuels. This means that every computer, lightbulb, and heating system in a school adds to the building’s carbon footprint unless steps are taken to use electricity from renewable sources.

Embodied carbon is less obvious. It consists of the greenhouse gases created by the carbon emissions it took to build and furnish the building and to dispose of the materials at the end of their lifecycle. It’s a long chain—extracting the raw materials from the earth; manufacturing, refining, or fabricating them into building materials; moving the materials to the construction site; running the construction machinery to install them; and tearing the building down at the end of its lifecycle and reusing, recycling, or landfilling the remains. It also includes the carbon-based fuel it took to manufacture, ship, and install the building’s mechanical equipment, appliances, architectural design elements, and furnishings.

The design and construction industry has become skilled at calculating how much electricity, oil, or natural gas a building uses during its lifetime. However, it’s harder to determine how much gas was burned to run the backhoes and cranes during construction, to make steel beams and plaster, or to manufacture the carpet squares that will go in a space. Current estimates suggest, however, that the embodied carbon generated in the year or two leading up to occupancy is as significant a portion of a building’s total carbon footprint as 10 to 20 years of operational carbon.

Once construction is complete and the building opens, there’s no way to reduce its embodied carbon. But the impact can be reduced by working with your design team during the beginning of the planning stages to choose lower embodied carbon materials. While this adds extra work, a 2021 report found that reductions in the range of 19% to 46% of upfront embodied carbon added little to no additional cost to construction.

To learn more, read IMEG’s executive guide, “Decarbonization in Education: A Practical Approach for the Built Environment.”

Or read other blogs in this series.

- 7 Reasons to Decarbonize Your K-12 and Higher Education Buildings

- Decarbonization Projects Start with Assessing and Optimizing

- Decarbonizing Schools Means Turning to Electricity and Integrating Renewable Energy

- Several Strategies can Reduce Embodied Carbon